When we trace the soundtrack of Los Angeles, we find it inseparable from the genius of Black musicians who transformed not just a city, but American culture itself. From the jazz clubs of Central Avenue to the birth of West Coast hip-hop, Black artists have been the architects of sounds that defined generations.

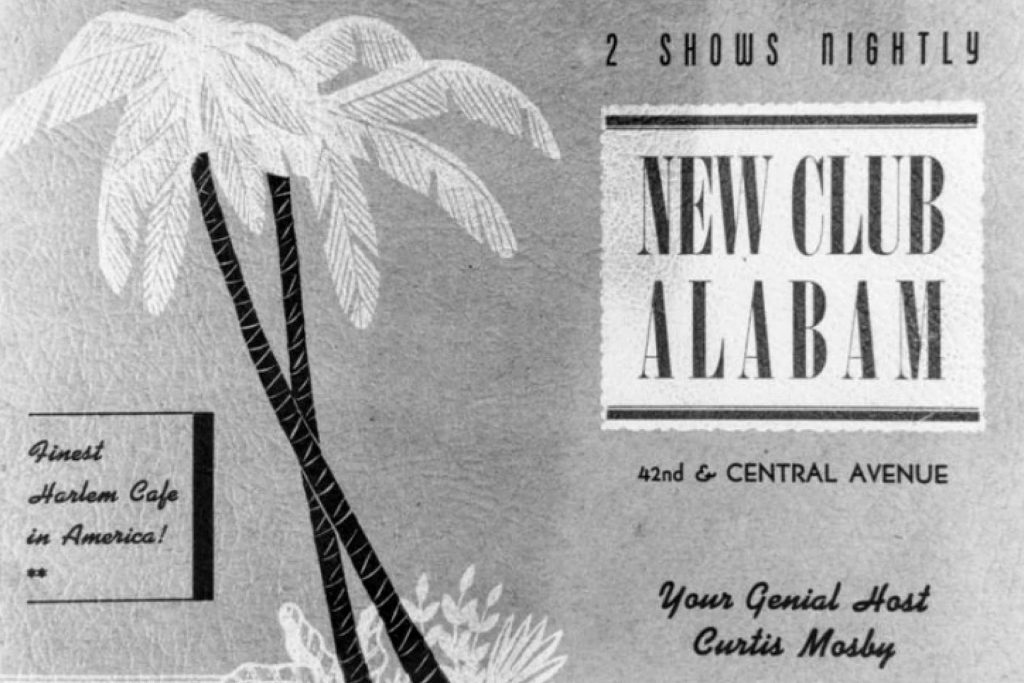

In the 1920s through 1940s, Central Avenue became the “Harlem of the West”— a thriving corridor where legends like Charles Mingus, Dexter Gordon, and Art Pepper honed their craft. The Dunbar Hotel hosted Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday, while the Club Alabam and Last Word Café pulsed with bebop and swing until dawn. Despite facing Jim Crow-era segregation that barred Black musicians from performing in many white establishments, Central Avenue flourished as a space where artistic innovation knew no boundaries. Here, musicians experimented freely, creating the West Coast jazz sound that would influence music worldwide.

The 1960s brought seismic shifts. Following the Watts uprising, artists channeled pain and resistance into new forms of expression. The Watts Prophets pioneered spoken-word poetry that would directly influence hip-hop. Meanwhile, Motown opened its West Coast operations, and artists like The Temptations recorded hits that captured both joy and struggle. South Los Angeles became fertile ground for funk and soul, with bands like War blending Latin, rock, and R&B into sounds uniquely Angeleno.

Then came hip-hop. In the 1980s and ‘90s, Compton and South Central gave birth to West Coast rap, with N.W.A., Ice-T, and later artists like Tupac Shakur and Kendrick Lamar using music as both mirror and megaphone for Black Los Angeles experiences. These weren’t just songs—they were documentary evidence, historical records of systemic inequality, police brutality, and community resilience that mainstream America often ignored.

The Leimert Park Village emerged as a cultural anchor in the 1990s, with the World Stage nurturing jazz musicians like Kamasi Washington and Thundercat, whose contemporary work carries forward the experimental spirit of their Central Avenue predecessors. This intergenerational continuity demonstrates how Black musical innovation in Los Angeles isn’t history—it’s living tradition.

These musicians did more than just entertain. They preserved culture during oppression, documented injustice before smartphones, created economic opportunities in redlined neighborhoods, and gave voice to the voiceless. Their melodies carried the Great Migration’s hopes, the Civil Rights Movement’s demands, and every generation’s dreams forward.

Today, when we hear jazz in a downtown club, bump hip-hop in traffic, or stream neo-soul, we’re experiencing the legacy of Black Los Angeles musicians who refused to be silenced, who turned pain into beauty, and who proved that even in a city built on illusions, the most real art comes from those who lived the truest struggles. Their contribution isn’t just to Los Angeles music history—it’s to the very soul of the city itself.